In the country where I grew up, music is a commodity, something presented to the audience disembodied, out of context, divorced from its original purpose, like an artefact in a museum. And it is performed as such, by expert musicians up on stages, admired by mute audiences. The idea of coming together to sing, of having a repertoire of songs for each season and occasion, is gone. We play ecclesiastical music out of churches, folk music divorced from its intended purpose and season, and we value technique above content and even above enjoyment. It has slowly dawned on me how very strange this would seem to my own ancestors.

If there is one word that describes the historical development of Western music, it is “commodification.” Our classical music was written for the enjoyment of the aristocracy. Written music replaced oral tradition, opera replaced ballad, and “folk” music was something to be curated and recorded by those few odd composers who took an interest. People learned music as a discipline from professional teachers, to a uniform standard and in uniform ways. The music on the page came to dictate the making of music rather than merely describing it. It was this kind of music that was taught in schools as education spread.

It is precisely in reaction to the vacuum this trend created in the public soul- at least insofar as the urban masses and non-specialists were concerned- that the movements of the twentieth century, and particularly jazz and rock, came into being. It was music that allowed for a sort of primal expression, manifested in raw emotion and free movement, that had been lost. It allowed musicians to play with their craft, to improvise and to step out of the old forms.

Scots and Irish music today provide an interesting case study. The traditional music of both nations has revived in a big way after a long period of repression for both the music itself and the Gaelic language. This revival, unfortunately, has become institutionalised, with standardised ways of playing each instrument, standardised tuning, standardised exams and standardised grading. It is studied as a subject.

The musicians who were fortunate enough to come out of the strongholds of the traditional music and language know that this is not what the tradition is about. They learned the way their ancestors did- with a group of neighbours getting together to make music and pass down the songs. It was not a course of study, but something that was part of the society and happened organically. Each locality had its own style, its own tuning, its own repertoire. Someone from Co. Galway could go to Donegal and find musical common ground, or indeed to Edinburgh, and bring back new material, but the distinctions remained, because the music was always a living, breathing product of the society around it, just as much as it was a legacy of past generations. Until recently, there were bards in Ireland who could recite in full the ancient sagas of Ireland, learned under the tutelage of their predecessors. Unfortunately, like so many strands of Celtic learning, this one was too extensively disrupted to survive.

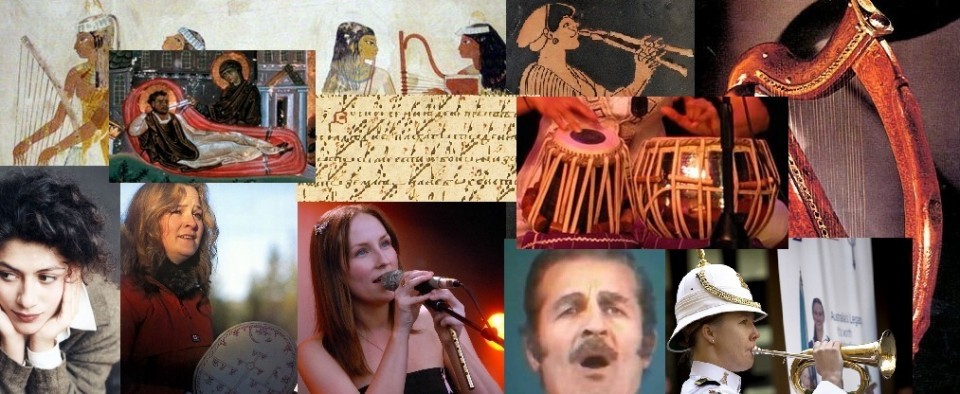

The habit of making music and telling stories as organic constituents of social interaction and community and not as professional mass-produced products is an essential part of the wellbeing of human communities- as witnessed by the fact that every other culture that has ever existed has probably done it more extensively than we do. We have a long way back, particularly in North America, where neighbourhoods as connected communities exist very sparsely. There are, thankfully, exceptions- but we urban North Americans have many attitudes to revisit before we can start making music in a really human way again- as a means of sharing culture and community and participating in the seasons and rhythms of life, performing music as a collective activity, not as theatre.

I see no small irony in the fact that I am assisting in the curatorial efforts of the modern musical scene, that I am presenting this music disembodied. But I do it from genuine appreciation and a desire to understand these different traditions and people, and to show what music is in these cultures, in hopes of showing what it can be again for my own.